"Manzanar: The Wartime Photographs of Ansel Adams" at Skirball Cultural Center

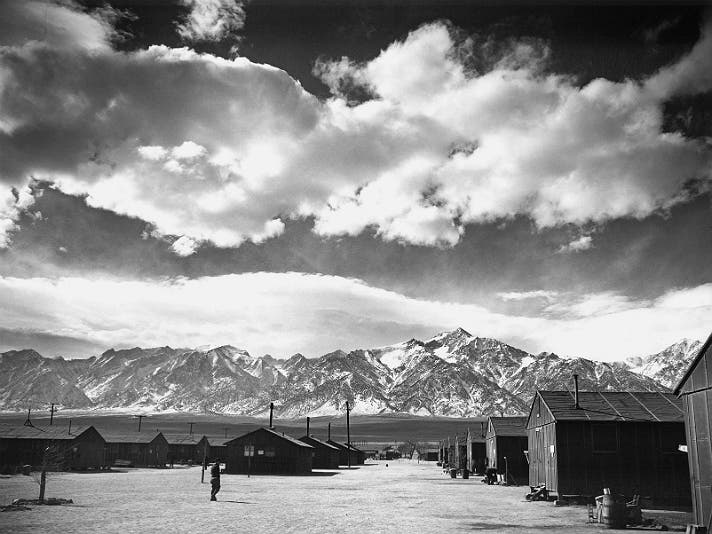

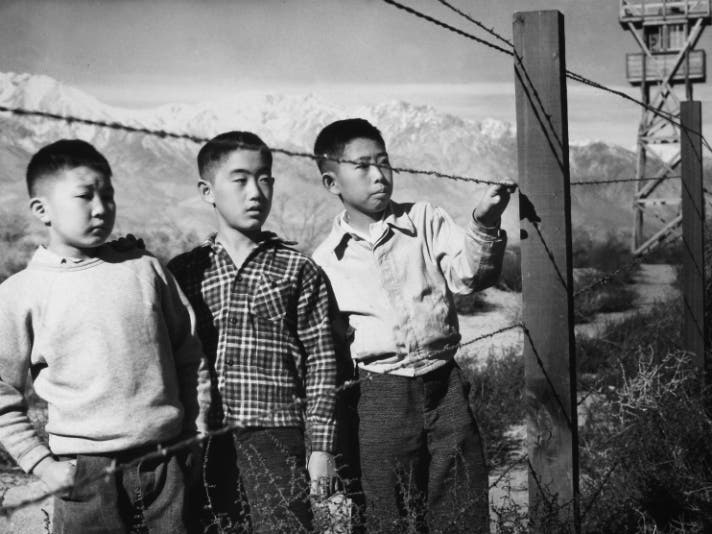

On view at the Skirball Cultural Center Oct. 8, 2015 – Feb. 21, 2016, Manzanar: The Wartime Photographs of Ansel Adams offers insight into a disquieting period in California and American history. The exhibit features 50 little-known photographs by celebrated landscape photographer, Ansel Adams (1902–1984) that depict the treatment of Japanese Americans at the Manzanar incarceration camp in central California. Taken during World War II, the black and white works were originally published in Adams’s book Born Free and Equal (1944) in which he protested what he called the “enforced exodus” of a minority of citizens.

今回は、ナショナルジオグラフィックによる「世界のビーチシティTOP10ランキング」にもランクインしたサンタモニカを取り上げます!

サンタモニカは、国内からも国外からも観光客が絶えない大人気のビーチエリアです。今回は、王道からは少し離れた、サンタモニカの歴史や文化を感じられる観光スポットを紹介していきます!それではさっそくいってみよう!

“Ansel Adams’s photographs of Manzanar bear witness to the resilience of the human spirit and the urgency of confronting injustice, embracing diversity, and preserving community,” says Robert Kirschner, Skirball Museum Director. “Powerful forms of civic and artistic expression, the images capture Adams’s steadfast message of compassion and tolerance, and call us to recommit to this nation’s highest democratic ideals.”

In the exhibition, Adams’s portfolio is complemented by the work of contemporaries Dorothea Lange and Toyo Miyatake, who also photographed Manzanar during the war. Also on view are documents, publications, propaganda materials, artifacts, and artwork detailing life and conditions at the camp. Manzanar: The Wartime Photographs of Ansel Adams was organized by Photographic Traveling Exhibitions of Los Angeles and is being presented at the Skirball in association with the Japanese American National Museum.

All exhibitions, including Noah's Ark at the Skirball™, are included with Skirball Cultural Center admission. Pricing is $10 for general admission; $7 for seniors (65 and up), full-time students with ID, and children over 12; $5 for children ages 2–12. Admission is free to Skirball Members and children under 2. Admission is free to all on Thursdays.

Read on for highlights of Manzanar: The Wartime Photographs of Ansel Adams as well as the companion exhibition, Citizen 13660: The Art of Miné Okubo and a schedule of related public programs.

Exhibition Overview

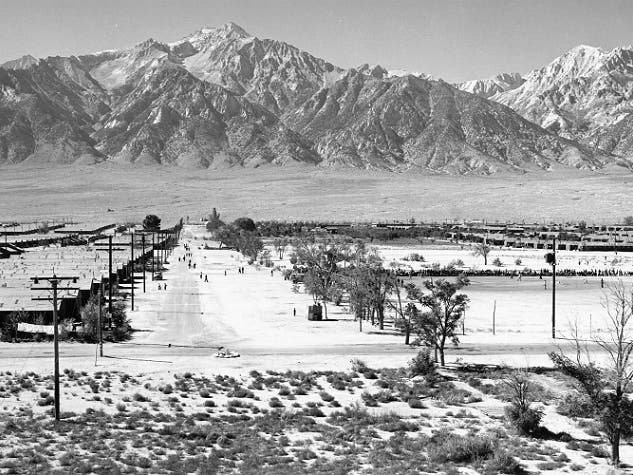

Located about 220 miles north of Los Angeles, the Manzanar War Relocation Center was the first of ten camps established to detain approximately 120,000 individuals of Japanese descent in the wake of the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. Pressured by the fear and paranoia sweeping the nation, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing the Secretary of War to “exclude” any residents from prescribed West Coast military areas in order to protect “against espionage and sabotage.” The majority of Japanese detained were native-born Americans or legal residents. Ultimately, Manzanar held 11,070 individuals, more than 90% from Los Angeles.

The exhibition opens with vivid examples of anti-Japanese propaganda, including cover art and articles from prominent publications such as Collier’s, LIFE, Vanity Fair and Time. The pre-evacuation period is observed in numerous photographs that Dorothea Lange took for the War Relocation Authority in 1942, one year prior to Adams’s own visit to Manzanar. Lange’s poignant images - many of them “impounded” for negatively portraying the government - document Japanese Americans being forcibly relocated, leaving behind shops and schools, boarding crowded trains, and encountering primitive living quarters at the camp.

Highly regarded for his majestic landscapes, Ansel Adams was already an accomplished fine art and commercial photographer at the onset of the war. In 1943, his friend Ralph Merritt, director of the Manzanar War Relocation Center, invited Adams to document life at the camp. While several views of the austere Eastern Sierras recall Adams’s signature subject matter, the majority of Adams’s images focus on people and their day-to-day lives at Manzanar.

Many portraits show individuals in their professional attire - as military personnel, a nurse, an artist, farmers, an electrician, among many others. Other photographs depict individuals engaged in various activities, such as baseball, Sunday school, a science lecture, working the potato fields, and standing in line at the mess hall. Adams also took photographs of several editions of the camp newspaper, the Manzanar Free Press, which was published by the incarcerated Nikkei (Japanese Americans). All Adams photographs on display were produced from original negatives in 1985 by Adams’s longtime printer, Alan Ross.

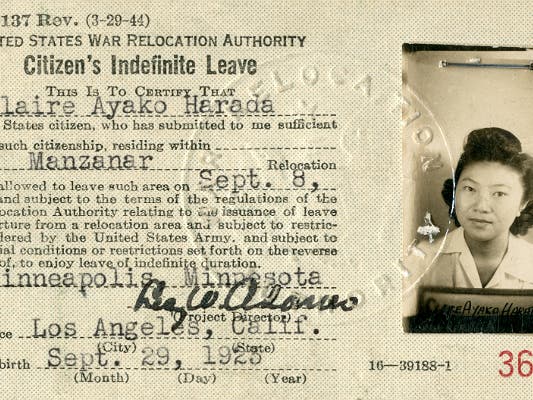

Later sections of the exhibition chronicle day-to-day life at Manzanar. Incarceration records and identification cards represent how those at Manzanar lost their full rights and protections as American citizens. Other objects illustrate efforts to lead a “normal” life, including a movie ticket, senior prom program, and artwork made at the camp. Schoolchildren’s essays, video interviews and home movies offer individual narratives.

In contrast to Lange’s and Adams’s depictions of Manzanar, the photographs by Toyo Miyatake, who was incarcerated there with his family, provide an insider’s record of the experience. Shooting surreptitiously at first, Miyatake eventually became the official camp photographer.

The final section of the exhibition documents Japanese American acts of resistance. Newspaper articles cite fatal riots, and a legal brief is an example of lawsuits filed to protest incarceration. Several items relate to the prosecution of members of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, a group of young men who refused to cooperate with the military draft without first having their basic rights as citizens restored.

"Citizen 13660: The Art of Miné Okubo"

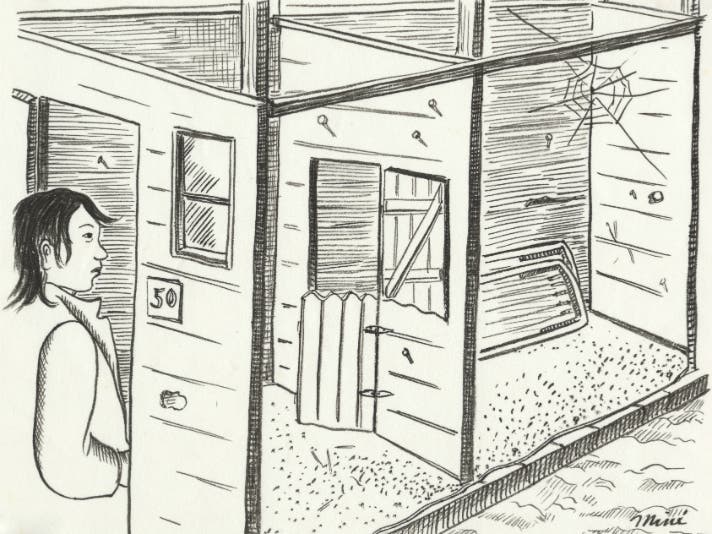

Also presented in association with the Japanese American National Museum, Citizen 13660: The Art of Miné Okubo explores the life and work of artist Miné Okubo. This companion exhibition to Manzanar: The Wartime Photographs of Ansel Adams centers on the graphic novel Citizen 13660, an illustrated memoir Okubo’s experience of incarceration during World War II. Originally published by Columbia University Press in 1946, the volume is the first account of life in a camp from the perspective of an incarceree.

A resident of Berkeley, California, Okubo was given three days’ notice before she and her brother were forcibly relocated, first to the assembly center at Tanforan Racetrack outside San Francisco, and then to the Topaz Relocation Camp in Delta, Utah. 13660 was the government-issued number assigned to the Okubo family. In an effort to document the injustices of the camps, the young artist illustrated her two-year incarceration in more than 200 images, accompanied by witty, candid text. Okubo left Topaz in January 1944 for a job with Fortune magazine, and subsequently went on to become a successful illustrator in New York. Citizen 13660 was reissued by the University of Washington Press in 1983 and received an American Book Award.

Citizen 13660: The Art of Miné Okubo explores Okubo’s exceptional book through a selection of rare original artwork and archival material that bring her personal and historical narrative to life. In addition to her portrayals of wartime, the exhibition lays out Okubo’s professional career and participation in the redress movement of the 1970s and 1980s, seeking an apology and reparations from the U.S. government for the incarceration of Japanese citizenry.